[ad_1]

When David Cameron took over as leader of the Conservative party in 2005, he pledged to introduce a “green revolution”. He went into the next election with the slogan “vote blue, go green”.

Fifteen years later Boris Johnson, who once disdained some of Mr Cameron’s efforts, is singing an almost identical tune. He campaigned in the last general election on the very same phrase and over the past two months he has started to outline what he hopes is his version of a green makeover.

Mr Johnson effectively destroyed the political career of Mr Cameron when he spearheaded the successful Vote Leave campaign in the 2016 referendum — the former prime minister abruptly resigned the day after the vote to exit the EU.

But having finally completed the gruelling process of extracting the UK from the EU, Mr Johnson is now trying to occupy the very same green political space that Mr Cameron initially staked out for the Conservatives.

In December, the prime minister set out his 10-point plan for a “green industrial revolution” that he hopes will be at the core of his administration. Mr Johnson’s platform included several eye-catching policies, including £3bn of new investment and a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030.

The new raft of environmental policies reflects something of the political journey Mr Johnson has travelled since the early 2000s when, as editor of The Spectator magazine, he published covers attacking “big green bullies” and arguing “the world has never been a better place”. Later, he sneered that the UK was full of ineffective wind farms that would struggle to “pull the skin off a rice pudding”.

He barely disguised his scepticism as Mr Cameron, then Conservative leader, flew to the Arctic in 2006 to pose with huskies and warn about the threat of climate change. In the past, Mr Johnson has often seemed to echo the dismissive tone on the environment used by populist rightwing leaders, such as former US president Donald Trump and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, with whom he has often been grouped.

But since becoming prime minister, Mr Johnson has tried to reinvent himself as a green warrior. Even if there are many questions about the effectiveness of the policies he has outlined so far, he insists that low-carbon industry is at the core of his plan to “build back better” after the coronavirus pandemic.

For Mr Johnson, the green agenda has become a platform for most of his political and economic objectives. After the rancour of Brexit, it allows him to pivot back to the centre ground of British politics — especially now that he faces a much more effective Labour opposition under the leadership of Keir Starmer.

It also provides an economic strategy that holds the promise of jobs for the deindustrialised towns in northern England, which have recently shifted to the Conservatives, and which will play well in Scotland at a time when support for independence is growing.

And with the UK hosting both a G7 summit and a UN climate conference this year, it allows Mr Johnson to present the country as confident and forward-looking rather than narrowly nationalist — while also finding common ground with the incoming Biden administration, with which he is keen to build a strong relationship.

There are already signs that significant parts of Mr Johnson’s party are not so committed to the new agenda, which critics have tried to label as authoritarian and too expensive. But Ben Page, chief executive of pollster Ipsos Mori, says that the prime minister’s embrace of climate policies allows him to present a less strident public image after the Brexit years.

“By talking up his green agenda, Boris can reassure Conservative Remainers and some nonaligned centrist voters that he is not “Britain’s Trump” as the outgoing president of the US liked to call him,” he says.

Tory fissures

The Conservative party’s journey to embracing action on climate has been a long and erratic one. It began with Margaret Thatcher, who warned the UN General Assembly in 1989 of a threat “more fundamental and more widespread than anything we have known hitherto”.

“What we are now doing to the world, by degrading the land surfaces, by polluting the waters and by adding greenhouse gases to the air at an unprecedented rate — all this is new in the experience of the Earth,” the then prime minister said.

Chris Patten, the Conservative peer who was then the minister in charge of international development, says Mrs Thatcher was won over to the cause by seeing it through the lens of science.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here

“It was something about which she felt strongly — partly because she understood it and knew what the chemistry of global warming was. She also wanted to take on the argument that this was just a leftwing way of having a bigger state,” he says.

But soon after, a fissure opened up among Tories about whether green policies were compatible with their economic philosophy. “For the Conservative party, it was an uncomfortable issue because it required you to do all sorts of things like raising taxes on motorists or whatever, which Conservatives didn’t like doing,” says Lord Patten.

With Mr Cameron’s ascension to the party leadership in 2005, Conservative environmentalism returned. He was initially a notable enthusiast for the first Climate Change Act, legislated by the then Labour government to enforce tough carbon targets, opposed Heathrow’s expansion and sought to put a wind turbine on his Notting Hill home.

After entering Downing Street five years later, he rapidly soured on the agenda — complaining that “people have had enough” of onshore wind farms and reportedly tried to eliminate “green crap” from his government’s agenda. The 2010-15 coalition saw endless running battles as the junior Liberal Democrat partners tried to hold Mr Cameron to his green pledges.

Johnson’s green investment plan in numbers

£3bn

New investments pledged by the PM’s 10-point plan, which includes a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030

180m

Tonnes of CO2 the government plans to save between 2023-2032, slightly more than half the UK’s current annual emissions

68%

The target set by the No 10 for cutting UK emissions by 2030, building on Theresa May’s 2050 net-zero pledge

“Dave’s problem was not that he didn’t believe it but he was cautious about financial commitments,” says Greg Barker, former climate change minister, who was on that Arctic trip 14 years ago. “When we did the husky trip people thought ‘wtf’ and ‘what on earth are they doing’, most people hadn’t even heard of climate change then.”

When the Conservatives returned to power in 2015 with a small majority, his interest diminished even further — in part as a response to the rise of the climate-sceptic UK Independence party which posed a threat to Tory support on the right. Mr Cameron duly imposed a new moratorium on onshore wind — saying “people have had enough” of wind turbines.

The shift started during the shortlived administration of Theresa May. Although her time in office was largely devoted to firefighting Brexit, in the dying days of her government in 2019, Mrs May committed to a “net zero carbon” emissions target of 2050. It replaced a previous target of 80 per cent cuts over that same period.

That one decision is the cornerstone from which all of Mr Johnson’s present low-carbon policies derive. John Randall, who was Mrs May’s special adviser on the environment, remembers her as a keen birdwatcher who had been concerned about the melting of the glaciers. “She didn’t require much persuasion,” he says.

Surprise conversion

Since succeeding Mrs May in No 10, Boris Johnson has more overtly built on her green agenda. Stanley Johnson, his father and a longstanding Conservative environmental campaigner since the 1970s, thinks the prime minister’s rural upbringing instilled a belief in conservation. “Boris grew up on Exmoor surrounded by one of the most beautiful countryside spots you could conceivably imagine and has imbibed a lot of this [agenda].”

Some old colleagues have been surprised by Mr Johnson’s newfound enthusiasm about green matters. During his time as London mayor, he penned several columns for the Daily Telegraph questioning some of the science behind climate change — even if he did introduce electric buses, the “Boris bike” hire cycle and a tree-planting programme in the capital.

Other Tories think his change of heart is partly inspired by his fiancé Carrie Symonds, a staunch environmentalist who works for the climate change charity Oceana. “Boris has always been all over the place on the climate, but Carrie has convinced him he has to take it seriously. Now he speaks like he’s a member of Extinction Rebellion,” says one minister.

Whatever the reason, there are still plenty of gaps in the programme. The scale of the package when it was announced — £12bn, of which £3bn was new money — was small compared with other countries. Germany has a €40bn climate plan, while France has determined that €30bn of its budget will have a positive environmental impact.

In recent weeks, there have been questions about the government’s commitment to the green agenda, not least when ministers approved Europe’s largest new gas-fired power station proposed by Drax in North Yorkshire. The government also angered some greens when it gave the go-ahead to Britain’s first deep coal mine for 30 years, albeit to produce coke for steelworks rather than for power stations.

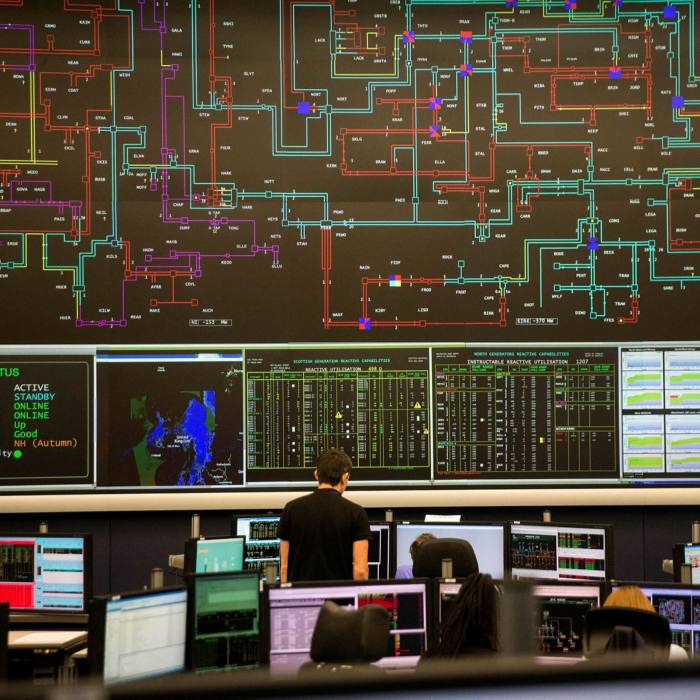

The government has yet to resolve the question of how the UK will tax carbon post-Brexit or upgrade its electricity network. Ed Miliband, shadow business secretary, says the funding “does not remotely meet the scale of what is needed” to tackle the climate emergency.

Chris Stark, chief executive of the Committee on Climate Change, the government advisory body, says the 10-point plan will help to cut emissions, but “doesn’t take us all the way to net zero,” which is the UK’s target for 2050. “It is a vision, it is not a plan,” says Mr Stark. “The following 12 months is [when] the real hard work needs to be done . . . It is a vision statement that we will need to see filled in with more detail soon.”

The government estimates the plan will save more than 180m tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions during the 2023 to 2032 period, which is slightly more than half the UK’s annual emissions right now. Mr Johnson has also announced that the UK would set a new, more ambitious target for cutting emissions by at least 68 per cent by 2030.

If the prime minister’s conversion to the green cause may seem a riddle to some, one explanation lies in the rapid fall in the cost of low-carbon electricity since 2010 — most dramatically in offshore wind power. Downing Street officials explain that a shift in the “raw economics” of green industry and energy has convinced sceptics there is no longer a dichotomy between the economy and the environment.

“The cheapest sources of power now are renewables,” one senior No 10 official says. “So if you want to make your businesses more energy competitive, if you bring down people’s bills, then you want to roll out more renewables. It’s undeniable it’s the right thing to do for our economy.”

The official adds that a strong green agenda would help Mr Johnson’s levelling-up agenda to address regional inequality. The prime minister argues that a low-carbon economy will bring jobs and investment to places such as Teesside or Sedgefield, the so-called “red wall” areas of England that voted Tory for the first time in the 2019 election.

“We think the future of the economy is a green economy and the way that you level up, the way that you re-industrialise a lot of these areas that have lost out over the last 30 years is through the new technologies that are coming through,” the Downing Street aide says.

Mr Johnson’s inner circle has also concluded that in the decade since David Cameron struggled with the issue, the impact of climate change has become apparent to Conservative and voters.

“The politics have moved on in part because we see the effects of climate change in our daily lives. We’ve obviously had, you know, much hotter summers and wetter winters. People are just more alive to the issues than before,” the official adds.

The departure of Dominic Cummings, the prime minister’s former chief adviser, has changed the dynamic in No 10 on green issues, especially with the increased influence of Ms Symonds. One senior Tory claims that “they [Mr Cummings and his allies] had a bit of an outdated view of where the economics and the politics really are”.

Mr Cummings and the other advisers from the Vote Leave campaign were wary of the threat from the right, notably from Brexit campaigner Nigel Farage who has pledged to challenge Mr Johnson’s environmental agenda. The leader of the Reform party responded to his 10-point plan joking, “this country voted for Boris Johnson and ended up with Caroline Lucas [leader of the Green party].”

But talking up his stance on green issues is seen by No 10 as a key way of shoring up the Tory vote in richer, metropolitan areas where it is vulnerable to both the Liberal Democrats and Labour party. One cabinet minister says: “It’s a way of smoothing off Boris’ image, reminding voters of the cuddly liberal figure that was London mayor.”

“Despite the pandemic, 2020 saw a rise in the proportion who think we are heading for disaster on climate change if we don’t act — now at 83 per cent in September, up from 59 per cent in 2013,” says Mr Page at Ipsos Mori. “It also is a key global concern and lets him roll out global Britain on an agenda that Joe Biden and President Xi [Jinping] both support in the year of COP26 [the UN summit].”

Yet that does not mean the party is united about the wisdom of embarking on such major structural changes to the UK economy when it is battling an annual deficit of nearly £400bn as a result of the pandemic.

It is not clear whether ministers are yet ready for some of the difficult conversations they may need to have with the electorate in the coming years — for example, the likely need for road pricing to replace fuel tax income if people switch to electric cars en masse.

One senior Tory who remains sceptical of the agenda says: “There are much cheaper and more effective ways of levelling up. I think people might move on from greenery when other challenges — especially Covid — mount.”

However, Stanley Johnson is hopeful that the UN summit in Glasgow will mark the moment that the Tory party settles its decades-long debate on the environment and his son concludes Margaret Thatcher’s mission.

“The Boris period in office, I hope, can stand tall in terms of its environmental record,” he says. “That’s one of his big challenges.”

[ad_2]